Have you ever been working on a project and wondered ‘why are we doing this’? You’re not alone. I always wonder about that.

Many times, stakeholders have an outcome in mind that they are expecting, but since they have a solution in mind as well, they skip over explaining what the goals of the project are. But, don’t be discouraged. Here’s a simple way to help you uncover the ‘why’ behind the ‘how.’

Enter Why Maps

Why maps are a way to ask ‘why’ over and over and over and map out your thought process as you do it.

Why maps are simple in concept: Start with your project and ask ‘why’ – why are we doing this project? Then ask why to the answer you gave. Keep doing this until you question the nature of reality. Don’t ask how, or who, or what, only ask why.

Ask the obvious: Why are we doing this project? Why do we need engineering resources to build this? You’ll know the answer, but the ‘whys’ you ask to those answers may be what open up a better understanding of the project needs.

I think of it like uncovering a video game map – there won’t be a stash of ammo and stimpaks in every area, but you’ve gotta check out those parts of the map to know for sure. And eventually, you’re going to find something really useful.

Making your map

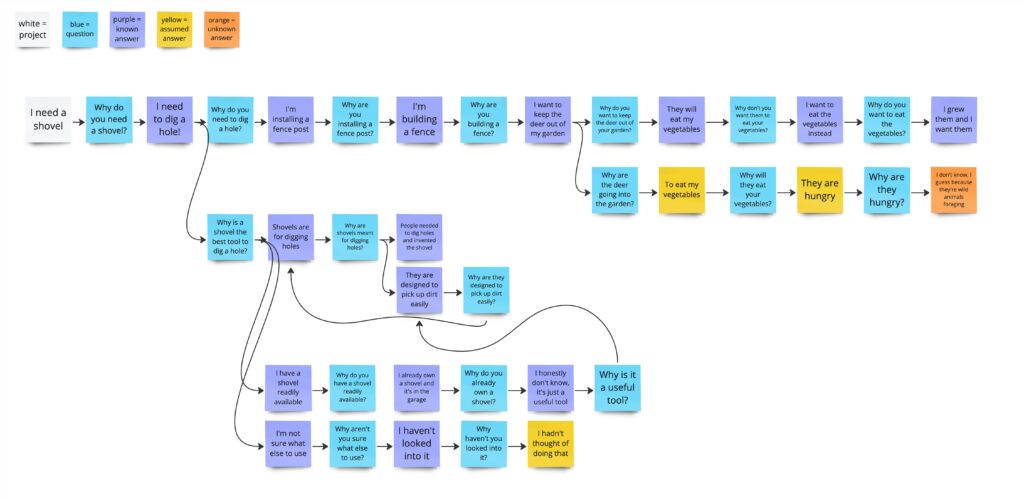

I use Miro to create my why maps, using colored sticky notes to denote questions (always starting with why), answers I know for sure, assumed answers, and unknown answers.

My why maps look like this:

They help to visually demonstrate where you have a deep understanding of the project, and where there are assumptions and unknowns. The bigger your why map gets without any assumptions or unknowns, the better you understand the project. The smaller the map, the less you know. Easy!

This allows you to explore the project and get a list of crucial questions to ask in 20 or 30 minutes. You can show your map to your stakeholders and show them where you need additional info, and maybe even get some ‘why’ questions from them as well.

An Example on How to use Why Maps

Let’s walk through an example of how a why map can be powerful.

Here’s the scenario from the why map image above:

I say ‘I need a shovel’You say…

‘Why do you need a shovel?’

>

To dig a hole in my yard

>

Why do you need to dig a hole in your yard?

>

I’m installing a fence post>

Why are you installing a fence post?

>

I’m building a fence, duh

>

Why are you building a fence?

>

I’m trying to keep deer and creatures out of my garden

>

Why are you trying to keep deer and creatures out of your garden?Why do deer and creatures come into the garden?

>

I don’t want them to eat my garden plants

They want to eat my plants

>

Why do deer eat garden plants?

Why do you want to keep the deer from eating the plants?>

They are hungry and it’s easy food

I want to eat the food instead!

>

Why are the deer hungry?

Why is it easy to get the food?

Why do you want to eat the food?

>I’m not sure, I guess because deer are wild animals who can’t farm

The food is just sitting there, unguarded

I grew it, I want it!

Now we get into the space where we are questioning things that are pretty foundational. We can keep going, but we now have a much better idea of why the shovel is needed! And you understand that my real goal is keeping animals from eating my garden. You can help me solve that problem now, instead of just handing me a shovel and then having me get frustrated with you when…

The shovel isn’t really what I need. A post hole digger would be better. A dirt auger would be even better. Or I could opt for a fish line fence, which is often all you need to keep deer away. I could plant a sacrificial crop of something deer and creatures love to distract them from my garden. I could spread blood meal and predator urine to scare the creatures off. I could opt for container gardens on my deck where the animals won’t eat them. I could do a few of these things! There’s so many options!

This comes from a real-life scenario where I was putting up a fence for my garden, and had a really hard time digging up the stony dirt to get the posts in. I ended up using a whole variety of tools to get the job done, and none of them were a shovel. This is why it’s so crucial not to assume you know what is needed without fully understanding the situation the solution exists in.

In Conclusion

I have many times been asked to design a feature without understanding the ‘why’ behind it, and often once I uncover the effect the feature is meant to have, the solution changes entirely. I was once asked to combine two screens together to make navigation easier for users – but when my team looked into why users were having trouble with this screen, we uncovered an entirely different workflow that was slowing people down. All users needed was a button to download some information, not an entirely reworked experience. This solution ended up saving a lot of time and effort, and met the user’s needs much better than changing the screens would have. And it was because my team asked ‘why.’

Ideally when you make a why map, everything makes sense and the solution you’re asked to design is exactly what is needed. Then a why map becomes a way to quickly find out where you need to get up to speed on the project, and you can take a few minutes to ask any outstanding question you have about the work instead of slowly uncovering these over the course of the entire project.

But you may also uncover the real reason behind the task and discover better solutions to the core problem. Uncovering the reason behind the proposed solution also allows you to more quickly test the solution, and prove out whether or not it will meet the project’s needs.

So get out there and ask why!